Community-Led Conservation in KSWS: A Real-World Dilemma

Community-Led Conservation in KSWS: A Real-World Dilemma

Could you knowingly disrupt the illegal livelihood of your neighbour? Friend? Family?

For many on the front line of community-led conservation efforts across Cambodia, this question is not theoretical, it is daily reality. Disrupt the economic activities of loved ones, or disengage and watch as someone else tries.

Decades of deforestation and hunting have left Cambodia with severely reduced wildlife populations. Yet important pockets of biodiversity remain. One of the most significant is Keo Seima Wildlife Sanctuary (KSWS) in Mondulkiri Province, Northeastern Cambodia.

Keo Seima Wildlife Sanctuary: A Stronghold for Biodiversity

KSWS protects over 300,000 hectares of semi-evergreen forest and is home to more than 1,000 recorded species of flora and fauna. Among its most notable wildlife are:

- The world’s largest remaining population of Southern yellow-cheeked crested gibbons

- The critically endangered black-shanked douc langur

These species depend entirely on intact forest for their survival, making KSWS one of Cambodia’s most important conservation landscapes.

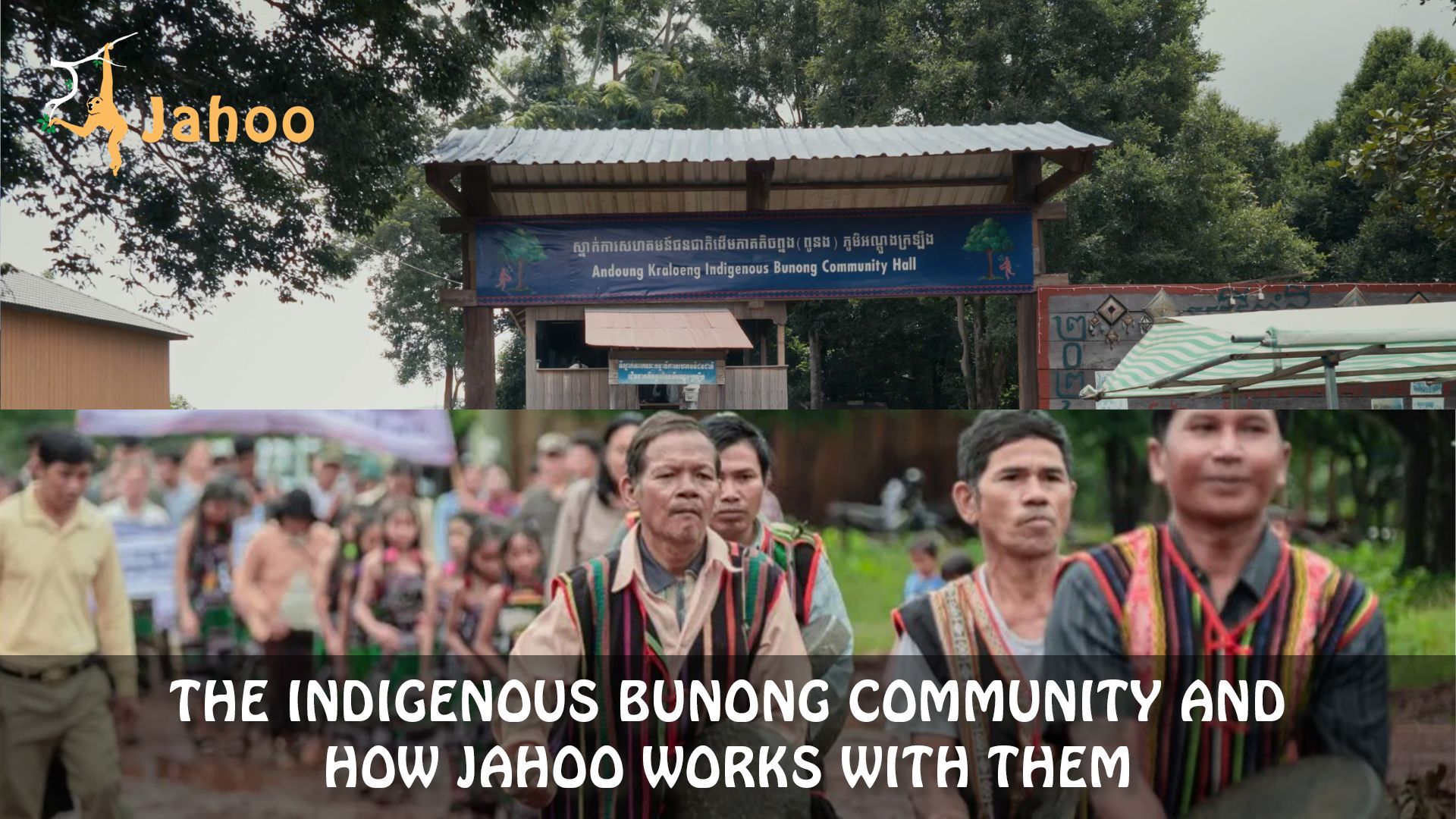

Indigenous Communities at the Front Line of Conservation

For nearly a millennium, Mondulkiri has also been home to the Bunong people, Cambodia’s second-largest Indigenous group. Around 21 Bunong communities live in and around the sanctuary, placing them at the centre of conservation efforts.

Through collaboration between government authorities, conservation NGOs, and community leaders, Bunong community patrol teams now play a critical role in protecting their ancestral forest.

Wildlife Decline and the Snaring Crisis

Despite protection status, wildlife in KSWS continues to face serious threats. A 2022 Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) survey revealed:

- Most terrestrial mammal species are in decline

- Snaring, hunting with dogs, and habitat loss are the primary drivers

- Once-common species such as wild boar and muntjac deer now number only in the hundreds

- Population declines of 60–80% over the past 12 years

Snares often made from motorbike brake cables are cheap, easy to set, and indiscriminate. Long snare fence lines can stretch hundreds of metres, acting like landmines for any animal that crosses their path.

The Moral Dilemma of Community Patrols

Community-led conservation is widely promoted as a solution, but it brings complex social challenges. What happens when the individuals setting snares are family members, friends, or neighbours?

“I’ve told my family, if they lay any snares or traps here, I’m going to remove them from the forest.”

—

Community patrol member, Klun Ta

Limited economic opportunities push some community members toward illegal hunting or logging. This creates tension and can fracture relationships within small, tightly connected villages.

How Community Patrols Are Supported

Community patrol teams are funded through a mix of:

- Local ecotourism revenue

- Nature-based and wildlife-watching tourism

- Conservation NGO programmes

- Long-term support from the EXO Foundation, which over the past two years has provided funding, capacity building, and operational assistance to strengthen patrol effectiveness in Keo Seima Wildlife Sanctuary

Patrol members use their deep knowledge of the forest to remove snares, deter illegal activity, and monitor wildlife populations.

Changing Conservation Through Understanding

It is easy to view hunters solely as perpetrators. Harder but essential, is recognising the social and economic pressures that drive these actions.

“Our elders hunted selectively with crossbows or old guns. It required skill and patience. Now anyone can set a line of snares and catch everything.”

— Community patrol member, Pjel Vy

Long-term conservation success depends on trust, dialogue, and alternative livelihoods that allow communities to protect forests without sacrificing their economic security.

Conservation and Ecotourism with Jahoo

At Jahoo, conservation is inseparable from tourism. Community-led experiences such as guided forest treks, wildlife monitoring walks, and Indigenous-hosted stays directly support patrol teams and conservation livelihoods in Mondulkiri.

With continued collaboration and EXO Foundation support, these initiatives are helping reduce snaring pressure on wildlife while ensuring conservation benefits remain with local communities through shared tourism revenue.

Names have been changed to protect the identities of individuals.